Agtech Insights: The Importance of Strategics on Your Company’s Cap Table

Last November’s Thrive Global Impact Summit brought together several hundred entrepreneurs, investors, and senior executives in Silicon Valley for a day of debate around pressing issues in the agrifoodtech space.

While a plethora of timely topics were up for discussion, this article will zoom in on one of the key themes that stood out for me from across all of the day’s panels: the evolving investment landscape around agtech solutions, and how corporates and other strategic investors are central to scaling them.

Bear Market?

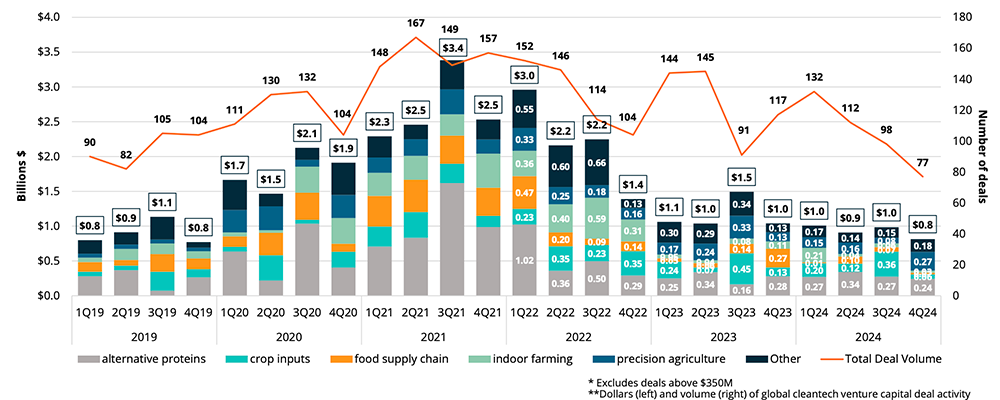

As reported in Cleantech Group’s recently published 2025 Global Cleantech 100 report, climate start-ups in Agriculture & Food raised a total of $3.7B in venture funding in 2024, down from the previous year’s $4.6B and a substantial reduction from $8.7B in 2022.

Agriculture and Food Venture Funding 2019 – 2024

Nevertheless, deal numbers were down only slightly from 2023, hinting that select investors still see opportunity in backing technologies that can future-proof food production.

While venture capital funds undoubtedly have a role to play in growing promising agtech and foodtech businesses, they are not always set up to align with the slower adoption timeframes and seasonal nature of agriculture. Many innovators in this area are now facing a scaling-up gap, and more patient capital will be required to take them to the next level.

Panelist Will Kaplan, director at agri-food-focused private equity firm Paine Schwartz Partners, told attendees that his team “sees more and more interest in this sector” from a variety of investors, though “aggressiveness around the pace of adoption curve has created some out-of-whack dynamics.”

EcoTech Capital’s Adam Bergman agreed that there has been unrealistic expectation-setting. “Based on my experience in broader cleantech, history tells you most of the new entrants aren’t going to [become] large public companies,” he said.

At Cleantech Group, we believe that the more likely route to exit for agrifoodtech start-ups will be through deep partnerships and eventual consolidation with incumbent corporates, who already have brand-name recognition among farmers and established market distribution networks built over many decades.

Other types of investors, with longer-term perspectives and more focused theses, will also have an increasingly important role to play in scaling up agrifoodtech innovation.

“They not only understand the markets, but also the adoption timelines. That’s one of the challenges; many of the [generalist VC] investors don’t know that,” Bergman said. “So, the capital is going to come from companies, from philanthropists, from pensions and sovereigns.”

The Strategic(s) Advantage

The idea of having corporates involved as investors from early on will go against the start-up instincts of many tech entrepreneurs and VCs, who often default to viewing themselves as disruptors in competition with incumbents, rather than their partners.

But a strategic investor is likely the best chance for agtech innovators get their solutions into the hands of their target end users. Panelist Jason Trusley, chief strategy officer at Land O’ Lakes, pointed out that his co-op works with about 300,000 farmers across the U.S.; a number far beyond the reach of a typical start-up, even with substantial time, effort, and spending.

“Sometimes you don’t want a strategic on your cap table — but you can’t afford not to,” added Hadar Sutovksy, vice president of corporate investments at fertilizer and chemicals company ICL. “Corporates actually create a win-win for start-ups, in terms of access to knowledge, to facilities, and go-to-market… We understand the industry because we are part of the industry,” she said.

PJ Amini, senior director of venture investments at Bayer’s corporate VC unit, Leaps By Bayer, went a step further, telling the audience that “the only thing better than having a strategic on your cap table is having more than one.”

Not only does this enhance the reality check that investors provide for entrepreneurs, by offering additional perspectives; it also has a multiplier effect leading to further opportunities for partnering and innovating.

A recent example is the three-way collaboration between start-up Innerplant, crop inputs incumbent Syngenta, and ag equipment maker John Deere, which is also an Innerplant shareholder. This partnership has seen Innerplant’s soybeans, which have been gene-edited to signal when they are at biotic risk, treated with optimized crop protection products from Syngenta applied by John Deere’s smart-spraying technology.

Opening Minds & Scaling Up

Incumbents nevertheless face their own barriers when it comes to investing in, or partnering with, agri-food entrepreneurs – as well as each other.

Again, one such barrier is presented by the ‘Silicon Valley mindset’: an excessive focus on rapid growth and the nitty-gritty of technology, at the expense of setting upon a business model and go-to-market strategy that can actually work in agriculture.

Panellist Scott Komar, senior vice president of global R&D at berry producer Driscoll’s, urged early-stage innovators to think ahead and try to anticipate their prospective customers’ needs. “How are they going to scale doing just what they’re doing already? So you’ve made three of these… how are you going to make 300?,” he asked.

“The other thing is scaling across. You made this really neat solution for managing powdered mildew on strawberries. What’s your plan for how this’ll work with table grapes, with tomatoes? We’re a global company. If we find something we like, we’d like that to work everywhere,” he said.

Beyond the high interest-rate environment and drive to cut spending across the board, structural issues around internal communication and company culture can also slow down corporate investment into agri-food innovation.

“Internally, if you don’t have alignment, if there’s not good internal collaboration, then you won’t have good external collaboration,” said Todd Stucke of tractor manufacturer Kubota. ‘Not-invented-here syndrome’ – an apprehension to engage with external innovation from start-ups, research institutions, or other corporates – was also pinpointed as a prevalent problem by Bayer Crop Science’s Dan Ruzicka.

An 80-year-old firm offering irrigation and windmill equipment, Valmont Industries was involved in one of agtech’s biggest exits to date with its $300M buyout of crop monitoring start-up Prospera Technologies in May 2021. Vice president Trevor Mecham was on stage to offer insights for fellow corporates looking to invest or acquire in the space.

“It’s an interesting position to be in, particularly as an infrastructure company; you build something that’s going to be there for the next 25 to 30 years. How do you adapt an old company from a machine shop to evolve into a tech provider? While there is consolidation [in agri-food tech], it’s also upon us as incumbents to collaborate and bring that together,” he said.