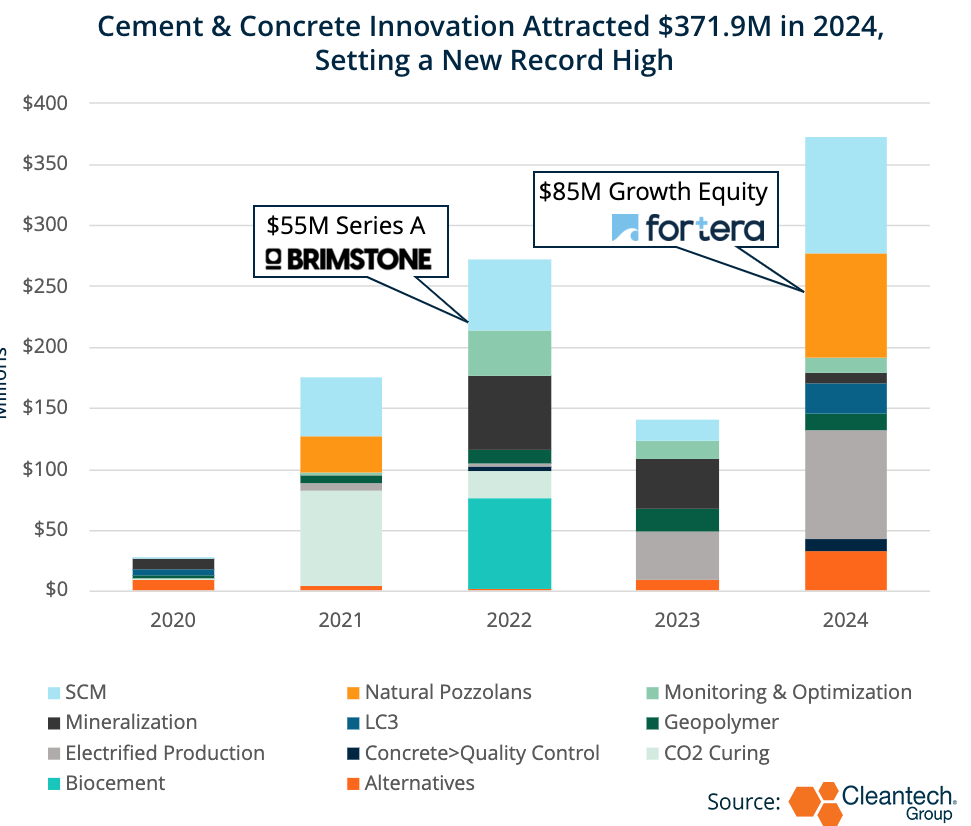

Record $371.9M Raised for Low-Carbon Cement in 2024, But $20B Needed by 2030

Cement Produces Unavoidable Emissions

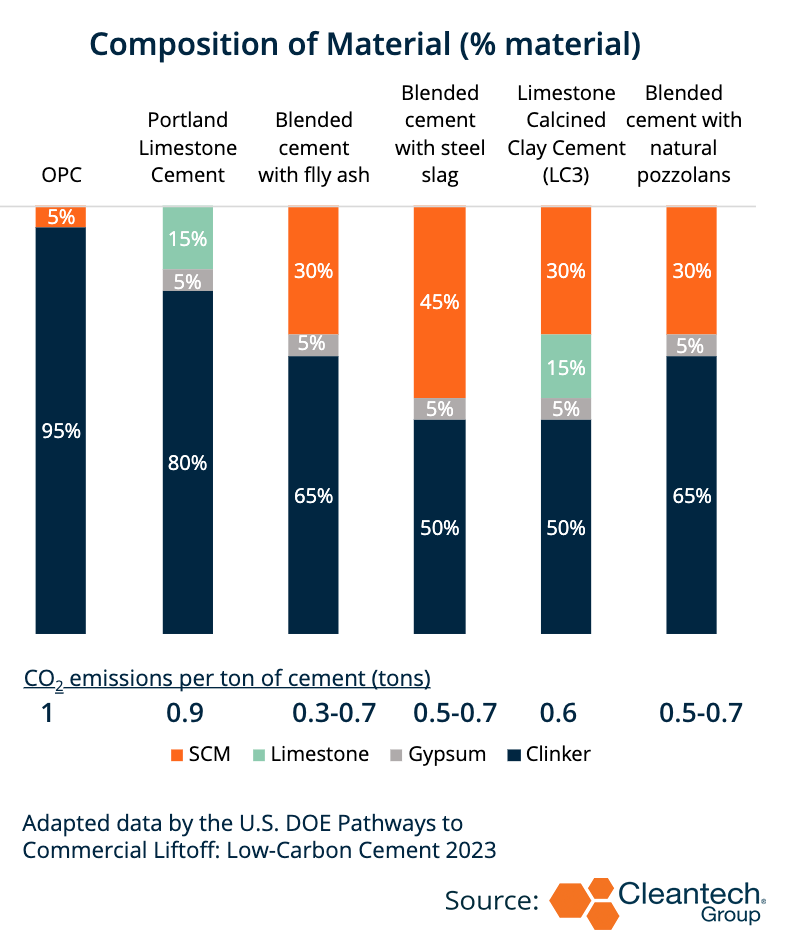

Second only to water, concrete is the most consumed material on Earth with an annual production of approximately 4 billion tons. The industry is responsible for 7% — 8% of global anthropogenic emissions and over 3% of the total global energy production. Ninety percent of concrete’s emissions come from its primary ingredient, cement, that produces 1 ton of CO2 per ton of cement.

While leading producer companies report plant-level data, tracking 100% of emissions from the industry is currently unfeasible. 60% of emissions are due to limestone calcination where limestone (CaCO3) decomposes into CO2 and lime (CaO). An additional 40% of emissions come from the burning of fossil fuels to reach kiln temperatures of 2,000° C or more, and other small steps.

Solutions at various stages of development are emerging but are not on track to meet net-zero by 2050. The industry aims to reduce 20% of CO2 emissions per ton of cement and 25% of CO2 emissions per ton of concrete by 2030. In 2022, the reduction of CO2 per ton of cement was only 2.2%, well below the target. To meet these goals, cumulative investments of $20B by 2030 are required for low-carbon cement solutions and $60B — $120B by 2050, says the Global Cement & Concrete Association (GCCA).

The good news is, we tracked a record-breaking year in cement innovation in 2024. The top solutions include but are not limited to clinker substitutes, alternative fuel sources, and carbon capture.

Clinker Substitutes

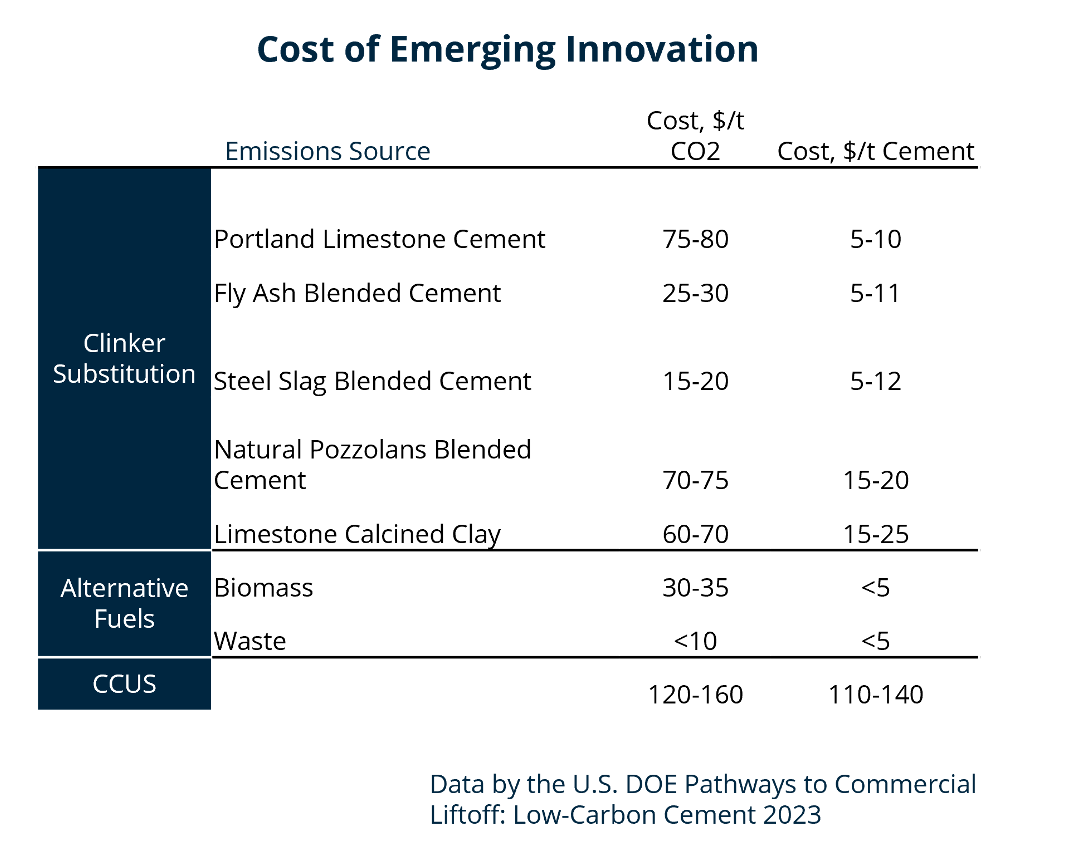

There are maturing and commercially deployed solutions that integrate industrial materials from mining, construction, demolition, hazardous and even agricultural waste. These substitutes are known as Supplementary Cementitious Materials (SCMs) and there are hundreds of examples. Conventional cement ranges from $30-$80/ton whereas low-carbon cement is $65-$130/ton. Low-carbon cement averages a 75% premium compared to conventional cement. Use of other widely available and cost-effective sources like low-grade clays or natural pozzolans (volcanic rock) are popularizing.

Carbon Upcycling sequesters CO2 into reactive feeds including crushed glass, fly ash, and steel slag for utilization in concretes and other high-value products like plastics and coatings. It is currently piloting its technology at CRH’s Canada Mississauga cement plant after receiving investments from CRH Ventures in 2023. Carbon Upcycling is also piloting its technology with Holcim, CEMEX, TITAN Cement Group, and others.

Alt Fuels & Electrification

These fuels may be derived from a blend or the complete use of industrial waste materials, by-products, or biomass. They add $5-$10/ton cement on average and are at a TRL 9. Other low-carbon fuel sources like green hydrogen produced via electrolysis are exceedingly expensive with a TRL 5-6, but may one day have an impact.

Electrification is near a TRL 3, but while still early in development, it can significantly offset carbon emissions by up to 40% — 87% or more when used in combination with pre-calcined raw materials. Exact electrification costs are difficult to calculate due to various parameters that are specific to location and output but can be 27% — 45% of the total cost per ton of cement.

CemVision reuses industrial waste as a raw material, typically from steel slag and mining waste, and uses electric ovens or plasma. It’s recommissioning failing cement plants across Europe by retrofitting with electrification and then producing its low-carbon cement. CemVision is nearing a pilot demonstration in 2025 with a 4,000 ton per year capacity.

Carbon Capture

Point Source Capture (PSC) for industrial emitters is a commercially deployed solution available to the cement industry right now. Unless you’ve got $1B to build a capture facility, then PSC is the most viable and only option. This technology is scaling rapidly with more widescale adoption to come in the early 2030s. Other capture technologies like Direct Air Capture (DAC) are significantly more expensive and will not ramp up until the 2040s. The largest and first capture facility specifically targeting cement emissions began operations in January 2024 at CNBM’s facility in Qingzhou Zhonglian, China with a 200,000 ton per year capacity.

Carbon capture can be integrated, as in the case of Leilac. Its technology heats limestone via a special reactor where furnace exhaust gases are kept separate from process gases. This enables the capture of pure CO2 as it is released from limestone. There is also potential for electrification of calciner to reduce the emissions from fuel. Leilac is deploying a first-of-a-kind facility together with its parent company, Calix, in South Australia to produce near-zero emissions lime and supply captured industrial CO2 emissions to the Solar Methanol Project for the creation of low-carbon transport fuels for the shipping sector.

Carbon capture may also be performed post-combustion to capture the emissions from flue gas. Ardent’s gas separation technology using membranes can precisely filter CO2 from flue gas. Its technology is compact and modular, fitting inside any cement facility. It has even discussed deploying its technology in a Capture-As-A-Service (CaaS) model wherein emitters don’t have to front high capital expenditure. Rather, Ardent will act as a capture service provider. It’s raised over $16.5M from Solvay Ventures, Chevron Technology Ventures, Technip Ventures, and more.

High CAPEX and Few Economic Incentives Have Slowed Progress

Cement is a $410B industry, and the demand for it is set to increase, especially in developing regions in Africa and Asia. Meeting those growing urbanization demands will require even more scale up of the current capacity. Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC), the traditional cement composition, is considered the only material to meet these demands. This is due to the wide availability of an important and cheap ingredient, limestone.

It’s no coincidence that metropolitan cities are always within an earshot of a limestone mine or quarry. This co-location helps bring down the cost of transport and storage to the areas with highest demand. But this has resulted in regionally fragmented markets (generally a 200 km radius) dominated by only a few incumbents who have near-complete control over their respective supply chains. Only 3% of the global cement production was low carbon cement material in 2023, meaning that 97% of the market is waiting to be targeted, according to the International Energy Agency.

For innovators deploying clinker substitutes, they must be co-located near a quarry via partnership with a demand owner. Without it, scale up of commercial volumes over 300 thousand tons per year will never be economically viable. This means there will eventually be significant consolidation to account for the geographic restrictions, similar to the mineral mining industry. Currently, there are no projections of low carbon cement materials ever being able to meet the demands of urbanization in these areas.

In regions with access to cheap and reliable sources of renewable energy, we will see electrification, electricity, or plasma, will take off in the 2040s, according to the Energy Transitions Commission. But in other developing regions, electrification will be significantly too costly for widescale adoption. In these regions, alternative fuels from agricultural waste and other sources will emerge as viable alternatives to fossils. Incumbents like CEMEX and CEMENTA have already begun integrating biofuels. Similarly, green hydrogen is a potential fuel source. But high-ticket costs for electrolyzers mean uptake in the near-term is unlikely.

Cement is an Infrastructure Problem

After reading Deb Chachra’s “How Infrastructure Works,” I began to understand more of the complexities facing the essential systems within the cement and concrete industries. Building out any infrastructure is a monumental task, especially with limited financing options for new facilities or lack of support from the public sector, just a couple of barriers that low-carbon cement solutions are facing. But why change the fundamentals of cement production when all we really need is to decarbonize the material and its production methods—easier said than done!