Solvent Dissolution, Next Gen Advanced Plastic Recycling

The State of Plastic Recycling

Plastic production is expected to double by 2050. Similarly, plastic-related emissions are expected to double by 2060. Sustainable disposal of plastic waste presents an especially daunting challenge as the annual volume of plastic waste is set to triple by 2060. With the mounting volume of plastic waste and related environmental impact, where do recycling technologies fit in curbing this growing issue?

Plastic’s recycling rate has plateaued at around 8% globally for several years. Some countries with comprehensive waste infrastructure like South Korea, Germany, and other European states have achieved recycling rates over 50%, yet the global nature of plastic waste cannot be mitigated by these outliers nor by the limited nature of the incumbent technology, mechanical recycling.

Mechanical recycling, an energy efficient and widespread process, specializes in recycling PET and HDPE. The process is severely limited in recycling other plastic types (it degrades PVC and PP while LDPE often causes damage to machinery). Furthermore, mechanical recycling produces contaminated recyclate as ink, dyes, or additives are not removed in the process. Contaminated recyclate garners a lower market price as its applications are severely limited.

Novel recycling technologies labeled “advanced recycling,” a series of physicochemical processes extracting monomers or polymers from plastic waste, promised to overcome process inefficiencies of mechanical recycling. Have they lived up to this promise?

The advanced recycling market grew rapidly in the last five years, resolving some of mechanical recycling’s technical gaps and falling short in others. The first two methods to be commercialized, pyrolysis and depolymerization, broke polymer chains down into monomers or shorter chains. Both have use cases in the future (pyrolysis excels in converting mixed waste into fuels while depolymerization has already established dominance in PET recycling), but neither process matches the scope (how many types of plastics can be recycled) and efficiency (the output from recycling) of solvent dissolution, the newest generation of advanced recycling innovation.

Solvent Dissolution Innovations

Solvent dissolution is a unique form of physical plastic recycling that separates contaminants like dyes, adhesives, or metal from plastic using a solvent mixture, leaving a pure polymer to be reused. Two primary pathways have emerged and can be classified based on what the solvent targets in this process:

- Delamination: Utilizes solvents to dissolve adhesives between polymers or metal (multilayer plastics, solar panels, battery casings, car panels, aluminum packages). Delamination represents the first commercially viable method to recycle multilayer packaging while capturing all constituent parts, often including the dissolved adhesive. The diverse range of applications also improve plastic recycling in ignored waste streams like automobile or battery waste.

- Selective Dissolution: Uses solvents to separate polymers from contaminates, dyes, and additives. Selective dissolution expands plastic recycling to every plastic-containing waste stream, including textile waste. Innovation in the selective dissolution process includes the use of supercritical liquids that manipulate properties of liquids and gasses, radically improving efficiency and reaction speed.

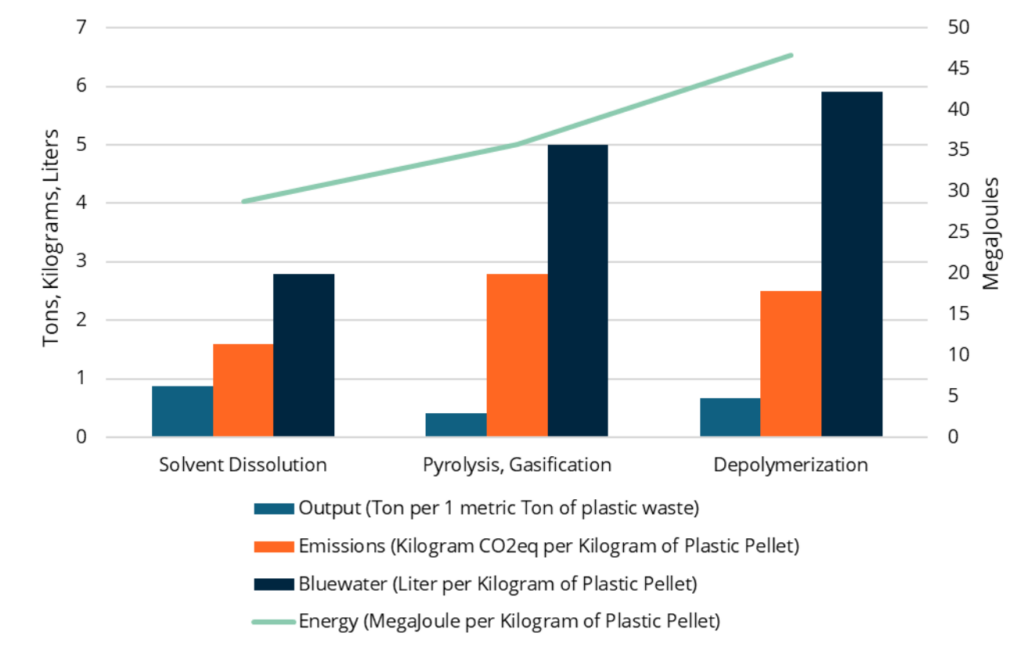

Solvent dissolution purifies polymers from surrounding waste without deconstructing them to their base monomers, unlike pyrolysis and depolymerization. Figure 1 represents the benefit of retaining polymers’ chemical structure; by eliminating downstream refining, solvent dissolution substantially reduces process emissions, energy requirements, and water use compared to pyrolysis and depolymerization. The environmental benefits of solvent dissolution do not compromise output volume either with an estimated 50% and 26% output volume improvement compared to pyrolysis and depolymerization (across all plastic applications).

Figure 1: Advanced Plastic Recycling Performance & Environmental Impact

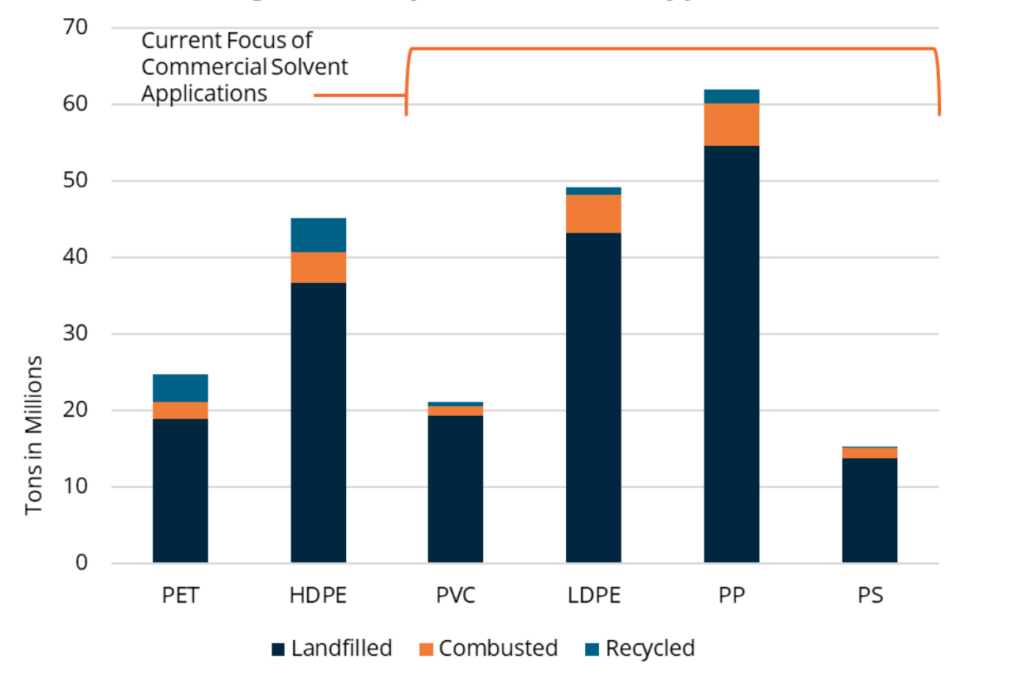

Solvent dissolution also iterates on pyrolysis’ promise to broaden the scope of what plastics are recycled. While solvent dissolution does not target multiple plastic types at once like pyrolysis, the diverse range of solvents on the market enables endless applications across plastic types (Figure 2). Academic research has been especially fruitful in identifying new solvent-polymer combinations. Companies like Purecycle and Polystyvert introduced first-of-their-kind commercial processes over the last few years targeting polypropylene and polystyrene, two plastic types previously without commercial recycling pathways. Solvent dissolution will prove particularly important in accelerating recycling rates for plastic types long ignored by conventional recycling, particularly in shipping applications.

Figure 2: Disposal of Plastic Types

Acronym list: PET – Polyethylene Terephthalate, HDPE – High Density Polyethylene, PVC – Polyvinyl Chloride, LDPE – Low Density Polyethylene, PP – Polypropylene, and PS – Polystyrene. Type 7 excluded due to difficulty in tracing and high variation in category of plastic.

Solvent Dissolution Innovator Spotlight

- Polystyvert: PS and ABS recycler utilizing cymene oil as an organic solvent. Company capitalized on PS’ issues with degradation in mechanical recycling and a lack of attention toward ABS. With low solvent toxicity and high output, Polystyvert’s recyclate reduces GHG emissions by over 90% compared to virgin plastic.

- Purecycle: Arguably the largest commercial solvent dissolution recycler, Purecycle commercialized supercritical butane for PP recycling. After leasing their core technology from Proctor & Gamble (P&G), Purecycle has now established their flagship first-of-a-kind facility in Ironton, Ohio producing 49,000 tons of PP recyclate annually.

- APK: Recently acquired by LyondellBasell (LYB) in August, APK is the first commercial multilayer plastic recycler. By integrating air-jet sortation in their processing, APK can process several multilayer packaging types at their facilities, but they specialize in LDPE, PP, and PA. After encountering financial difficulties in scaling their facilities, LYB’s acquisition should fuel a new era of expansion for the company.

Solvent Dissolution Trends and Long-Term Outlook

In terms of economics, plastic recycling remains more expensive than virgin plastic production. Recycled PET, bolstered by mechanical and depolymerization technologies, is now price competitive with virgin PET. For solvent dissolution to reach commercial maturity and price competitiveness in long-ignored plastics like PVC, LDPE, PP, and PS, it must emulate success stories from PET recycling. Commercial recyclers should seek out corporate partnerships with fast moving consumer goods (FMCG) corporates seeking to improve their product’s end-of-life outcomes. Key examples from PET depolymerization include Coca-Cola and Nestlé.

University research is playing an incredibly important role in commercializing solvent dissolution. Chemical Upcycling of Waste Plastics (CUWP) is a partnership of six universities, a national laboratory, and 23 companies simultaneously commercializing pyrolysis, depolymerization, and solvent dissolution technologies in an integrated supply chain. At the core of the partnership is a focus on commercializing the University of Wisconsin, Madison’s research on Solvent-Targeted Recovery and Precipitation (STRAP), a specialized form of solvent dissolution targeting multilayer plastic and Conductor-like Screening Model for Realistic Solvents (COSMO-RS), a computational model that calculates the solubility of target polymers.

More than just a standalone recycling process, solvent dissolution-targeting contaminants like dyes or adhesives can be used as a pretreatment in mechanical recycling, depolymerization, and pyrolysis. Dissolution pretreatments improve recycling process reactivity, increase recyclate purity, and reduce energy consumption, water use, and emissions. That said, solvent dissolution has key process issues too. The solvents and anti-solvents used in the process are very expensive. Breakeven economics usually require a 70%+ reuse rate for these chemicals. While a high expense today, innovation in chemical exploration could eventually eliminate anti-solvent requirements through switchable hydrophilicity solvents.

Solvent dissolution’s commercial development and incumbent interest is complicated. Part of the slow corporate engagement is due to supply chain immaturity. As recycling offtake was built around PET and HDPE recycling, waste managers and sortation companies have not developed systems to sort out all plastic types. As a result, recyclers are demanding a feedstock not yet available at scale. Investors also remain wary of advanced recycling after commercial failures in pyrolysis and depolymerization, slowing investment toward commercializing solvent dissolution.

That said, corporates like Sulzer and investors including Infinity Recycling, have been actively investing in start-ups like Worn Again Technologies and Polystyvert. Furthermore, Dow, Mitsubishi, P&G, and Braskem are partnering to research new solvent dissolution technologies with a particular interest in computation technologies accelerating solvent exploration. LYB’s acquisition of APK also signals incumbent interest in scaling the technology commercially through outright acquisition, not investment or partnership.

Solvent dissolution is not a magic bullet, but it does substantially improve plastic’s recyclability and environmental impact. Solvent dissolution’s fit alongside current commercial recycling technology and as a standalone option earns it the well-deserved label of advanced recycling’s second-generation technology.